Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017: CBO Report Facts

The Essentials From the CBO report on the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017

Get the facts on the CBO report on the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (the Senate’s ObamaCare repeal and replace plan AKA TrumpCare).[1][2]

UPDATE 2019: This plan never passed, and thus some specifics here are of historical interest only.

A Quick Overview of the CBO Report on the Better Care Reconciliation Act in Its Different Iterations

The Better Care Reconciliation Act Reconciliation Act has went through a number of changes in the Senate. On this page we compare the CBO’s scoring for the first version and the July 13th version with the Ted Cruz Amendment added in.

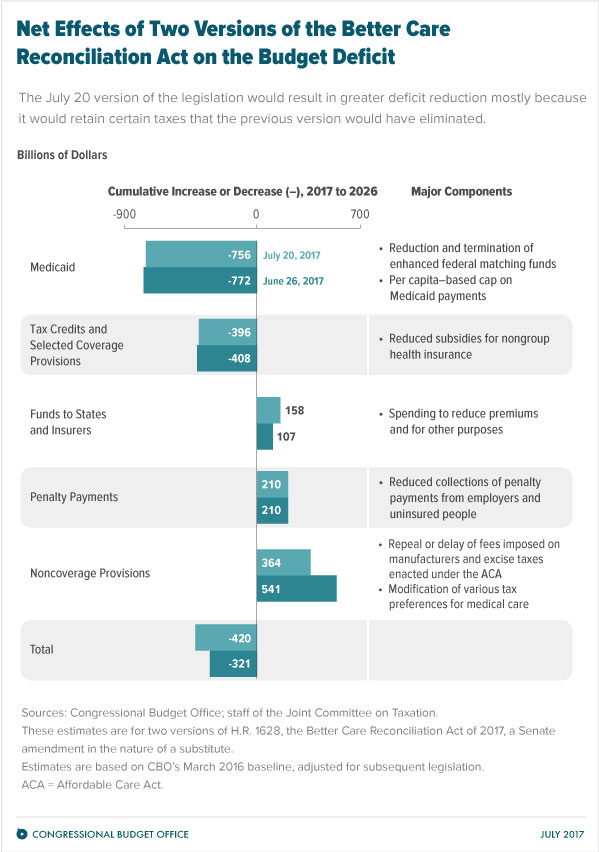

Thus we will be comparing the CBO’s May 24, 2017 report to the CBO’s July 20, 2017 report. The graphic above shows this comparison as well.

“Compared with the June 26 cost estimate for a previous version of the legislation, this cost estimate shows savings over the next 10 years that are larger—as well as estimated effects on health insurance coverage and on premiums for health insurance that are similar.”

- READ the First Version: The Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (AKA TrumpCare AKA the Senate ObamaCare bill).

- READ the BCRA as it stood July, 13th 2017 (the latest version): the full text of the Revised Senate Health Care Bill 7/13/17. See also “the Ted Cruz Amendment” (this is now part of the BCRA).

- CBO Report of the First Version: H.R. 1628, Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017.

- CBO Report of the Latest Version: H.R. 1628, Obamacare Repeal Reconciliation Act of 2017.

- Overview: See our page on the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017.

The Essential Facts From the CBO Report on the Senate HealthCare Bill – July 20, 2017

Below are essential facts about the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 from the latest CBO report (the July 20th, 2017 CBO report) with some commentary.

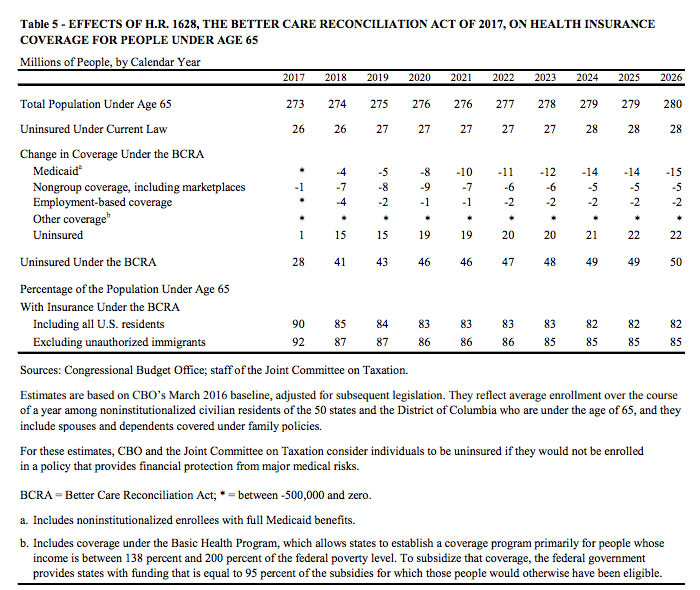

- CBO’s July 20, 2017 report: CBO and JCT estimate that enacting the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 would reduce federal deficits by $420 billion over the coming decade and increase the number of people who are uninsured by 22 million in 2026 relative to current law (for a total of 49 million uninsured; about what it was before the ACA’s coverage provisions took effect).

- According to CBO and JCT’s estimates, in 2018, 15 million more people would be uninsured under this legislation than under current law. The increase in the number of uninsured people relative to the number under current law would reach 19 million in 2020 and 22 million in 2026. In 2026, an estimated 82 percent of all U.S. residents under age 65 would be insured, compared with 90 percent under current law.

- The above reduction to the deficit by 2026 is the net result of a $903 billion decrease in direct spending partly offset by a $483 billion decrease in revenues.

- The agencies estimate that the provisions dealing with health insurance coverage would reduce deficits, on net, by $784 billion (i.e. cuts to cost assistance, small business tax credits, Medicaid, and the elimination of the mandates). The noncoverage provisions would increase deficits by $364 billion, mostly by reducing revenues (i.e. elimination on taxes on industries like tanning solons and drug makers).

- The largest savings would come from Medicaid cuts. By 2026, spending for that program would be reduced by 26 percent.

- The largest increases in deficits would come from repealing or modifying tax provisions in the ACA that are not directly related to health insurance coverage, although this is notably less true now that provisions repealing a surtax on net investment income and repealing annual fees imposed on health insurers have been removed.

- CBO and JCT anticipate that, under this legislation, nongroup insurance markets would continue to be stable in most parts of the country. This legislation would, by CBO and JCT’s estimates, increase average premiums in the nongroup market before 2020 and lower them thereafter, relative to projections under current law.

- In general what happens with premiums is the most complex part, to summarize the next paragraph premiums go up and then they go down… but in part due to lower benefit plans being sold. Under this legislation, in 2018, average premiums for benchmark plans for single policyholders would be about 20 percent higher than under current law, mainly because the penalty for not having insurance would be eliminated, inducing fewer comparatively healthy people to sign up. In 2019, those premiums would be about 10 percent higher than under current law—less than in the year before in part because funding provided by this legislation to reduce premiums would have a greater effect and because changes in the limits on how premiums can vary by age would result in a larger share of younger enrollees paying lower premiums. In 2020, average premiums for benchmark plans for single policyholders would be about 30 percent lower than under current law—a decrease brought about by several factors. Most important, this legislation specifies that benchmark plans would have an actuarial value of 58 percent (and, therefore, would pay for a smaller share of the total cost of covered benefits than the benchmark plans in 2018 and 2019). The effects on premiums would vary in different areas of the country. Also, even though average premiums for benchmark plans would decline, some people enrolled in nongroup insurance would experience substantial increases in the net premiums that they paid for insurance. For example, under this legislation, 64-year-olds could be charged five times as much as 21-year-olds, CBO and JCT expect, compared with three times as much under current law—resulting in higher premiums for most older people.

- For older people not eligible for premium tax credits, net premiums (after taking into account the tax savings from paying premiums from a health savings account) could be more than five times larger than those for younger people in many states, rather than only three times larger under current law. Because of such differences, CBO and JCT estimate that, under this legislation, a larger share of enrollees in the nongroup market would be younger people and a smaller share would be older people than would be the case under current law.

- To summarize the section on high deductible health plans, they will still be a hurdle under this plan. See page 9.

- Generally, as it was with the last version of the bill, the young, healthy, and higher earners fair well, those who are older, sick, or low-income could face struggles.

- In all, the current version of the legislation would result in greater deficit reduction mostly because it would retain certain taxes that the previous version of the legislation would have eliminated. However, the total uninsured remains the same.

Is the 22 Million Number Right?

There has been an assertion that the CBO is wrong and the 22 million number is wrong. With that in mind, the CBO has rarely been wildly off base with its projections. Despite that, to make sure you have all sides of the story, here are some caveats to consider:

- The CBO says, “compared with the previous version, this legislation would have similar effects on the number of uninsured people. Estimates differ by no more than half a million people in any year over the next decade.”

- Tom Price’s HHS predicted the Ted Cruz Amendment would lead to millions more covered than the CBO projected and lower premiums (mainly for healthy people who would benefit from low-benefit plans with annual limits). Assuming that is true, the basic concept here is the same: the BCRA saves money, deregulates health insurance (thus lowering plans for some), cuts taxes, cuts assistance, and results in millions more uninsured.

- It is important to note that some of the uninsured (but not all; see the graphic below) will be those who choose not to get coverage now that there is no mandate. Some in this group may, instead of not getting covered, choose a low-benefit, low-cost, Cruz plan (thus proving the CBO estimate high).

When the CBO predicts its uninsured or cost reductions they do so with the best data available to them. They look at each change, and then estimate the effects (which in this case are a reduction to deficit, reduction to revenue, reduction to spending, and an increase of the uninsured).

As you can see in the table below, when the CBO estimates the uninsured under the BCRA they look at the effects of each coverage provision. Given this, there is little doubt that the CBO estimates of the uninsured are accurate.

Even if every person on private coverage and employer coverage who loses their plan (or chooses not to have their plan) were to get a Cruz plan, 15 million would still lack Medicaid coverage by 2026.

The CBO estimates for uninsured under the BCRA.

The Essential Facts From the CBO Report on the Senate HealthCare Bill – May 24, 2017

Above we covered the latest CBO report.

Below are essential facts about the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 from the CBO report with some commentary. This will help you to understand what has changed and will offer some additional and relevant insight (because even though some things changed, the general concept of what is happening didn’t).

- CBO and JCT estimate that enacting the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 would reduce federal deficits by $321 billion over the coming decade and increase the number of people who are uninsured by 22 million in 2026 relative to current law (for a total of 49 million uninsured).

- To get this $321 billon surplus over a ten year period: $772 billion is cut in Medicaid spending and $408 billion is cut in assistance, meanwhile this spending cut over a ten year period is offset by decreased revenue over ten years which comes from $541 billion in tax breaks, $107 billion in spending to reduce premiums to insurers, and $210 billion less in mandate penalty payments.

- Of those 22 million who lose coverage (for a total of 49 million), it is 15 million less from reducing Medicaid funding and 7 million less from reducing cost assistance and getting rid of the individual and employer mandates (keep in mind 75% of families on Medicaid are working poor).

- The largest savings would come from Medicaid cuts.

- The largest increases in deficits would come from repealing or modifying tax provisions in the ACA that are not directly related to health insurance coverage, including repealing a surtax on net investment income and repealing annual fees imposed on health insurers.

- CBO and JCT estimate that, in 2018, 15 million more people would be uninsured under this legislation than under current law—primarily because the penalty for not having insurance would be eliminated.

- The increase in the number of uninsured people relative to the number projected under current law would reach 19 million in 2020 and 22 million in 2026.

- By 2026, among people under age 65, enrollment in Medicaid would fall by about 16 percent and an estimated 49 million people would be uninsured, compared with 28 million who would lack insurance that year under current law.

- Both the ACA and BCRA are projected to lead to stable markets (with some instability in specific regions). The CBO confirms the idea of a “death spiral” is a myth. It explains that “stability in most areas would occur even though the premium tax credits would be smaller in most cases than under current law and subsidies to reduce cost sharing—the amount that consumers are required to pay out of pocket when they use health care services—would be eliminated starting in 2020.”

- The legislation would increase average premiums in the non-group market before 2020 and lower average premiums after that, relative to projections under current law. In other words, premiums will go up at first, but average premiums will be lower down the road. This is mostly due to states being able to sell plans with fewer benefits under the BCRA. This shouldn’t’ be confused with the idea that customers will pay less or receive equal quality care. They won’t. Cost assistance would be reduced for premium assistance and eliminated for out-of-pocket assistance starting in 2020. Obviously, the 22 million excluded from the market will also not get “lower premiums” as they won’t have any insurance at all.

- Despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan due to reduced assistance and their inability to pay for premiums in the first place. So while tax credits offered to 0% – 100% FPL sound nice, they aren’t expected to be utilized by many Americans.

- The Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (AKA TrumpCare AKA the Senate ObamaCare bill). The actual bill.

- H.R. 1628, Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017. The CBO Report.